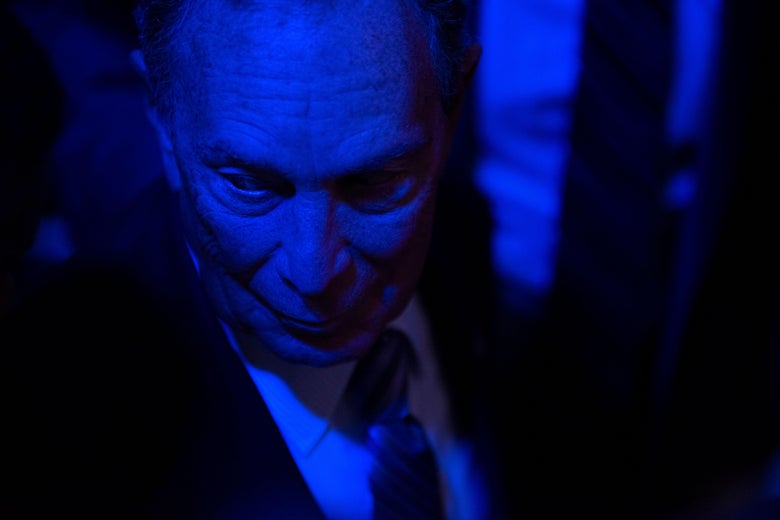

MARK FELIX/Getty Images

The morning after President’s Day, a new poll

found that Michael Bloomberg had captured enough public support to

claim a place onstage in the next Democratic presidential debate. On

Wednesday night, the business-information tycoon and former Republican

mayor of New York City will appear alongside candidates who have spent

months or years trying to win over Democratic voters—shaping their

policy proposals, cultivating armies of donors and volunteers, gathering

support door-to-door—having himself spent only money, a tsunami of it:

more than $400 million of his own fortune on campaign expenses,

including saturation ads across TV and online media.

It may look as if Bloomberg is simply joining the presidential race a

little later than the others. But what he’s really there to do is shut

down the presidential race entirely. Yes, everyone running wants to win.

But the other people in the race are asking voters to choose them.

Bloomberg is asking—or telling—the public to give up on the idea that

anyone really has a choice.

Everyone in and around the Democratic field shares the understanding

that Donald Trump represents a crisis of democracy. The candidates are

all, to a greater or lesser extent, running on the message that they are

each the singular person best positioned to resolve the crisis, by

defeating Trump and what he stands for: Bernie Sanders because of his

mass mobilization of supporters, Elizabeth Warren because of her policy

acumen, Pete Buttigieg because of his bright-eyed affection for unity,

Joe Biden because of his long-established public profile, Amy Klobuchar

because of her feisty moderation.

Bloomberg’s message is that it’s too late for any of that. Michael

Bloomberg is the only person who can beat Donald Trump, because he has

the power to beat Donald Trump, because he has the money. The voters’

preferences don’t matter. The crisis is too urgent for that. He alone

can fix it.

A broad swath of the media and political establishment is lining up behind this message of inevitability, just like it did last time. So far, this would-be consensus is struggling to overcome Bloomberg’s long and well-documented record: He is, after all, an enthusiastic authoritarian, and a sexist bully and boor. He ruthlessly wielded the power of the state against black and Latino people, and against Muslims. He’s a glib technology enthusiast who sees labor and craft as pointless and obsolete.

It is easy, but not sufficient, to point out that many of these

details line up with the reasons we’re supposed to want to get rid of

Donald Trump. Bloomberg has much more money than Trump, and he cuts a

much more respectable figure, but the two of them come from the same

cynical, domineering New York circles of power, and act like it. Not for

nothing is Trump a sometime Democrat, and Bloomberg a former

Republican. Not for nothing does each present himself as too rich to be

bought, even while the Trump Organization chases foreign development

projects and Bloomberg News killed its own coverage of high-level corruption in China to protect its access to the Chinese market for its moneymaking Bloomberg terminals.

If anything, Trump is the more honest participant in American

politics. Trump’s victory went against the popular majority, and may

have had foreign fingerprints all over it, but at least it respected the

basic theory behind a two-party contest. He roused the enthusiasms of

his party’s base and agreed, since it didn’t really matter to him, to

carry out the policy agenda of its elite supporters. The culture war

fans got their rallies and the Federalist Society got its judges,

and—apart from the griping of a few Never Trumpers who still choose to

care about administrative competence and are only comfortable with less

blatant forms of financial corruption—the Republican Party is basking in

the triumph of its chosen worldview.

On those terms, Bloombergism is a very different proposition than

Trumpism. Bloomberg’s offer to beat Donald Trump is an offer to do only

that, not to endorse or carry out the full agenda backed by Democratic

voters. The greatest hope of the anti-Trump opposition till now was that

democracy might yet assert itself—that the very narrowness of Trump’s

rule could produce a broad counter-movement, not just to sweep him from

office but to expand the range of voices and political possibilities, to

make iron-fisted minority rule a thing of the past.

Bloomberg, instead, is offering rule by a minority of one. Over the

weekend, the Times reported that in addition to the sudden and visible

flood of direct political spending, Bloomberg also boosted his single-year charitable spending

to $3.3 billion in 2019, buying goodwill and the silence of potential

critics across the country and around the world. The story opened by

describing how Emily’s List kept Bloomberg on its roster of speakers for

a fundraiser after he’d disparaged the MeToo movement. Feminist

advocates needed his money, even if it had to come at the expense of a

feminist cause. So, too, gun control activists could have his bottomless

support—as long as they made his top priority, background checks, their

own top priority, and they used the language he wanted them to use.

Government and policy are too important to be left to the people. This

is why gun control is Bloomberg’s ideal signature issue—it’s an area in

which the desires of large majorities of people are unable to prevail,

thanks to concerted and well-funded minoritarian efforts. Bloomberg

offers himself as an alternative power center, whose money makes it

possible for people to accomplish what they could never get done through

mere organizing and voting.

Perhaps this is why Bloomberg feels entitled to set the terms for

whatever movement he’s involved with. “Republican” and “Democrat” are

just labels to help him get in position; his patchwork identification as

a liberal carries no obligation for him to fill in the holes with what

liberals as a group may want. He does not have to distinguish between

mass preferences and his personal preferences. His ideological and

social priors say that charter schools are preferable to public

schools—innovation and competition are more dynamic than universal

institutional coverage—and so if you sign on with Bloomberg, you sign on

with charter schools. You don’t get universal health coverage, you get

limited soda sizes, and it’s for your own good.

Emily’s List needed Bloomberg’s money at its fundraiser, the Times

wrote, because it was happening in the middle of the fight over Brett

Kavanaugh’s nomination to the Supreme Court. Part of what made the fight

so desperate was that the Senate was controlled by a narrow Republican

majority; part of why the Senate was in Republican hands was that

Bloomberg had donated more than $10 million to Republican Pat Toomey’s

victory in a close race in 2016, because, while Toomey was a

right-winger who opposed reproductive rights, he favored background

checks. Forget other Democratic priorities. Supporting an ally on guns

was all that mattered.

Bloomberg doesn’t care about the overall alignment of power in

American politics, because his own power has never depended on it. The

only thing threatening to diminish Bloomberg’s power is the possibility

that Sanders or Warren might get elected president and bring enough

like-minded people along with them. To him, the true crisis of Trump is

that by devolving one of the major American political parties from

plutocratic to kleptocratic, the president has given the left wing of

the other party an opportunity to expand its influence. The proper

counter-move, for a responsible plutocrat, is to try to buy out the

opposition, to restore the nation’s former, politely unchecked levels of

wealth accumulation.

So he arrives late on the scene, in the guise of a rescuer. The open

secret of the crowded Democratic field is that most of the people

declaring how hard Trump will be to beat are, in fact, counting on him

being very beatable. He’s a nasty and unpopular buffoon who won while

being outvoted by a margin of 3 million last time, thanks to a fluky

convergence of the electoral map and the news cycles. There will be no

better chance, certainly not within what’s left of his lifetime, for an

elderly, charmless billionaire to claim the presidency.

Even with that, Bloomberg can’t claim it through the regular,

established methods. Our presidential nominating system is set up to be

perverse and unfair, but until now it did, at least, seem to offer the

same terms to every candidate. Sure, the Supreme Court had destroyed the

controls on campaign spending so that up-front money became an

overwhelming advantage, but a Bernie Sanders could counter it by

rallying an army of individual donors and celebrating how righteously

small their average contribution was. The Democratic Party could make

the number of individual donors a standard for debate access, and a

popular campaign could stay alive and funded till Iowa and New Hampshire

started caucusing and voting.

Bloomberg is trying to short-circuit all that—skipping not only the

donors but the voters, blowing off the first four states to try to win

Super Tuesday. The regular process, under which, at least in theory, any

qualified ordinary person could become president of the United States,

has been preempted by a process available only to someone with unlimited

personal funds.

And the Democratic Party, by removing the donor rules to qualify for debates, is obliging him (or welcoming him with open arms). Sitting senators like Cory Booker and Kirsten Gillibrand had to be winnowed from the debate stage, but who can say no to Mike Bloomberg?

And the Democratic Party, by removing the donor rules to qualify for debates, is obliging him (or welcoming him with open arms). Sitting senators like Cory Booker and Kirsten Gillibrand had to be winnowed from the debate stage, but who can say no to Mike Bloomberg?

Democratic self-rule has been at odds with the mass-media presentation

of politics for as long as mass media have existed. But a successful

Bloomberg bid, far more than Trump using his Apprentice notoriety to

devour free airtime on CNN, would mark the complete rupture between the

governed and the governing. Apart from a belated and inaccurate disavowal

of stop-and-frisk, Bloomberg is not pretending to have considered other

people’s opinions, or to have asked for their support, or to be honored

that they said yes. His goal is to market his way to a monopoly.

So why, fresh off a round of post-2016 self-reflection, do leading figures

in the media accept this from Bloomberg? Yes, he’s skipping the

contests where people cast ballots, but he’s advertising and provoking

commentary (like this) and moving up in the polls—the various realities

that matter to the political-coverage industry. Does it matter if the

point of his candidacy is that democracy as we’ve known it has already

failed, so the only answer to a rampaging billionaire is a billionaire

on a counter-rampage, or that popular goals can no longer be achieved by

popular means? Does it matter if his ruthless managerial skills failed

to budge the everyday troubles of New York—if the technocratic

problem-solver failed to fight the state over the MTA’s deferred

maintenance and general decline, failed to break the culture of

dysfunction in the housing agency, or did less than nothing for the homeless?

He put his name on the economic recovery, in a proprietary sans-serif

typeface rather than shiny brass letters. He was so uninterested in

other people’s needs or opinions, he made his own priorities seem like

necessity.

It’s true, as people feel compelled to say, he’s not as bad as Trump.

Single-minded profit-chasing is not as bad as a lifelong career of

high-stakes fraud. Allegations of harassment are not as bad as

accusations of rape. Life under a neoliberal control freak would almost

certainly be more comfortable than life under a thief and bully with a

taste for fascism. But to accept that argument—to take Trump as the

benchmark—is to surrender any claim on affirmatively setting the

nation’s political values. It’s to accept that the republic deserves

nothing more than what Michael Bloomberg is willing to give it.

Just listen to the people who fall outside Bloomberg’s vision of who

matters and what he’s responsible for. When he allegedly told an

employee who needed a nanny for her baby, “All you need is some black

who doesn’t have to speak English to rescue it from a burning

building,” he was making a racist and sexist remark, but those terms

might be too narrow to capture the comment’s full tone. It seemed,

principally, to be a joke about Bloomberg’s broad contempt for all

categories of human beings who are not wealthy white men. This was not

the panicky, Trumpy bigotry of Rust Belt Republicans, who organize their

lives around imagining a vision of blackness or foreignness to pit

their own identities against. It wasn’t the bigotry of the grasping or

the obsolete. It was the bigotry of security. Bloomberg’s story about

stop-and-frisk keeps changing because, in the end, he didn’t care one

way or the other about having the police jack up hundreds of thousands

of innocent young men. He only got angry when someone told him he wasn’t

allowed to do it.

Readers like you make our work possible. Help us continue to

provide the reporting, commentary and criticism you won’t find anywhere

else.

Join Slate Plus

Join

Join Slate Plus

No comments:

Post a Comment

Note: Only a member of this blog may post a comment.