A standard progressive complaint about K-12 education policy is that reliance on local property tax revenue creates an inequitable situation where the poorest communities have the smallest budget to hire teachers. This is, in practice, pretty outdated. States have changed their funding formulas significantly, so the biggest gaps these days are between high-spending and low-spending states, not between rich communities and poor communities within a particular state.

One area where things really do work that way, though, is policing.

Criminal law is mostly written by state legislatures, who decide which activities are crimes and what the rules of procedure in their court system will be. States set sentencing guidelines, and states run prisons. But actually enforcing the law is left up to county sheriff’s departments and the local police departments of incorporated towns or cities. This setup even allows for things like private police departments, often run by universities, which can have full powers of arrest. There are strengths and weaknesses to this model of localism, but the upshot is that policing resources are allocated largely by ability to pay rather than by any effort to assess actual policing needs. This raises fairness concerns, but also real questions of crowding out.

The Los Angeles Police Department, like many police departments these days, is falling short of its recruiting goals. Raises and signing bonuses have helped close the gap, but there are limited funds available for that kind of thing. Even if zero additional dollars were allocated to Los Angeles, if the police departments in Santa Monica and Beverly Hills and other rich suburban towns were to cut the size of their forces, that would mechanically make it easier for the LAPD to hire officers.

As I wrote last spring, even looking at the District of Columbia, where there are no questions about local funding, it seems like there are too many police officers working in low-crime rich neighborhoods and too few working in high-crime areas. If the topic at hand were anything other than policing, this would be seen as a clear social and economic injustice. And what I want to observe here is that precisely because the people who like to talk about inequality tend not acknowledge the impact of policing on crime, they’ve actually allowed a dramatically more inequitable situation to arise with regard to the distribution of law enforcement resources than we would put up with in almost any other area.

Baltimore is underpoliced

As I have complained on many occasions, the state of crime and law enforcement data in the United States is deplorable. If you want to know the answer to a question like “how many people were murdered in Maryland last year,” you can’t find out on a reasonable timeframe.

But if you go back to 2021, the last year for which the full FBI dataset is available, there were 709 homicides in the state of Maryland. Of those 709, nearly half happened in the City of Baltimore. The good news is Baltimore had a huge murder drop in 2023, but there’s no statewide numbers from 2023, so we’re stuck with the outdated data. The point is that back in 2021, a city with fewer than 600,000 residents (out of a state population of over six million) had a huge share of the murders. It’s harder to get reliable information on total shootings and other crimes. But I think it’s safe to say that murder volumes generally track with the overall volume of gun-related crimes, and that use of deadly force is almost always a symptom of other kinds of crime problems.

That’s all just statistical confirmation of what we all know from broad stereotypes: Maryland is a very rich, predominantly suburban state, and Baltimore is a low-income, high-crime city.

So what about police resources in the state of Maryland? Well, using BLS figures, the Baltimore Police Department employs about 30 percent of the state’s cops.

That’s a bit of an understatement of the real numbers, since some state police officers do work in Baltimore and there are some Maryland Transit Authority cops in the city, too. But it’s as close as we can come to a good estimate, and it can’t be off by nearly enough to account for the gap between Baltimore’s share of cops and Baltimore’s share of shootings.

If policing were a purely state-run function, it would be a no-brainer to reallocate personnel to the places where they’re most needed. You’d have more beat cops in Charm City crime hotspots and more detectives to keep working on unclosed murders before new cases force them off the docket. In exchange, response times for mostly not-that-important calls in the suburbs would go up. This would be a more fair result, and it would also lead to substantive improvements across the state. The downside is crime would probably go up in the jurisdictions with fewer cops. But you’d be trading a decline from a high base rate of crime against an increase from a low base rate, generating less overall crime. The state of Maryland as a whole, meanwhile, has a housing affordability problem. But Baltimore itself is cheaper. And beyond being cheaper, Baltimore has a lot of buildable land. Across much of Maryland, demand for housing is high, but it’s difficult or impossible to get permission to build. But in Baltimore, the city is planning to spend millions of dollars to try to deal with tens of thousands of vacant buildings and vacant lots. A large, sustained decline in crime would make the private sector eager to take those lots and buildings and invest in them — generating economic growth and tax revenue for the whole state.

Meanwhile, though cities and suburbs do face short-term tradeoffs, in the longer run it’s better to be a suburb of a thriving city than of a dying one. Reducing Baltimore crime, raising Baltimore housing demand, and snapping the cycle of population flight and economic decline would benefit everyone.

Lots of states are like this

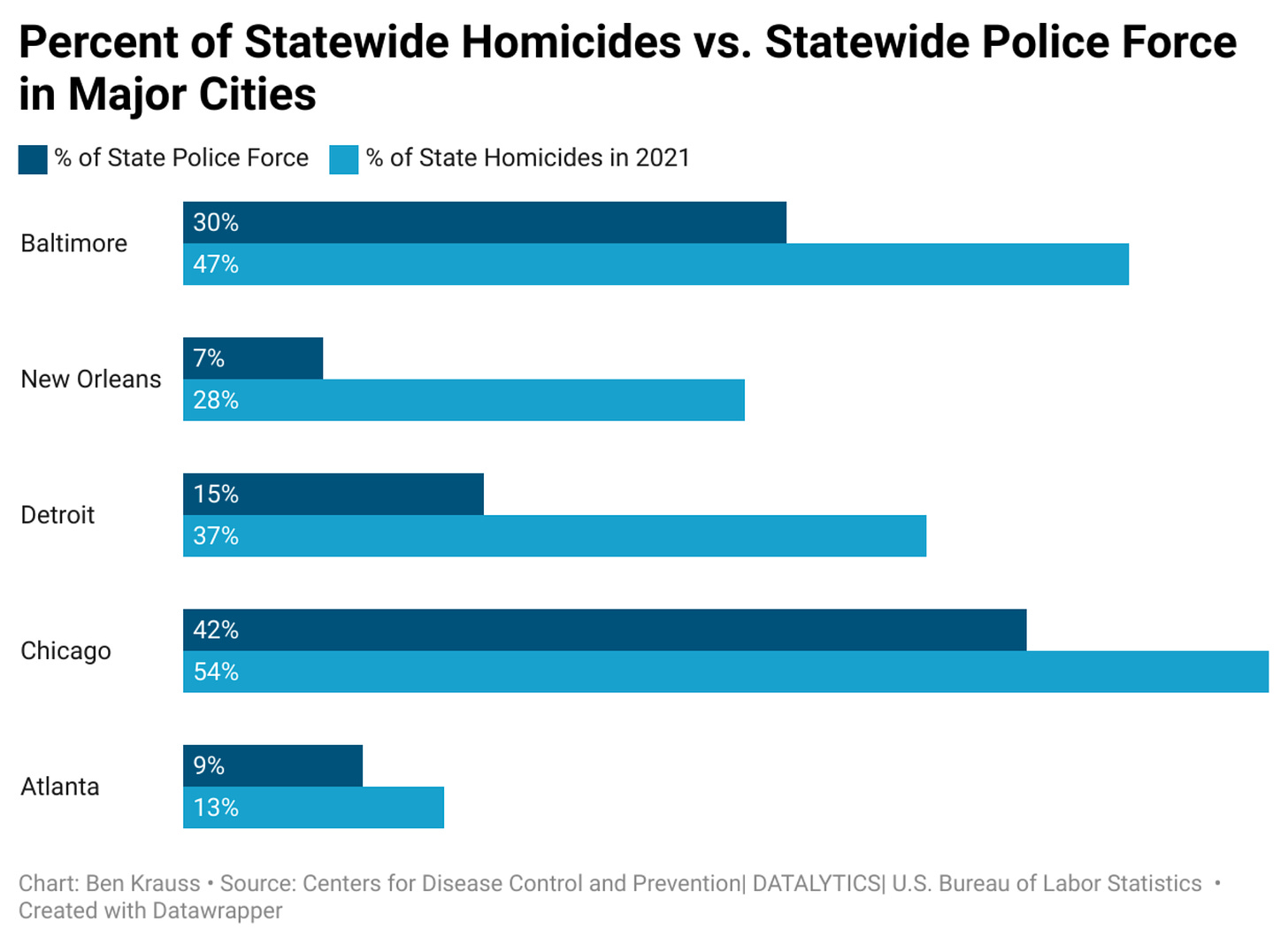

Unfortunately, the relevant data in this space is fragmentary, outdated, and a little annoying to work with, so it’s hard to do the analysis for every state. Instead, we picked five states — Maryland, Illinois, Louisiana, Michigan, and Georgia — that contain one-and-only-one large city. For those states we did a simplified comparison: What share of the state’s cops work in the one big city, and what share of the state’s murders happen in the one big city? We’ve got two blue states on the list, a red one, and two purple ones.

And we see the same pattern everywhere.

Obviously, characterizing the situation in a state like Texas, California, or Florida with multiple large cities would be more complicated. And then you have states like South Dakota with no big cities. Or states like Massachusetts where the one big city is unusually safe. So there are plenty of complications. But I think that what we see in those five states is a good rule of thumb for understanding the distribution of law enforcement resources in the United States. It’s pretty typical to have a central city that is relatively large, but poorer than its suburbs and with below-average income for the state. That city typically suffers from high crime and employs more cops per capita than the average jurisdiction, creating a large burden on taxpayers. But despite the burden of paying for all those cops, the large city is underpoliced compared to other jurisdictions in the state.

To an extent, that’s just a distributive tug of war — of course voters in the suburbs don’t want to pay for policing in Chicago and Detroit.

But there’s a real efficiency cost here. According to Aaron Chalfin and Justin McCrary, there’s an elasticity of murder with respect to police department size of -0.27 — in other words, you would expect a 10% increase in the size of a city’s policy force to generate a 2.7% decline in the number of murders. That means that especially in places like Louisiana where the distribution of officers is wildly unequal, you could generate a decrease in the total number of murders without spending any money by reallocating officers to where the crime is.

The larger dynamic, though, is that in most of these cases, I think quality of life issues in the central city are an important drag on the overall statewide economy. Most people don’t particularly want to live in central cities, but they usually do want to live near central cities, which aren’t just destinations for commuters but anchors for regional institutions like airports, hospitals, sports teams, and museums. I don’t think it’s a total coincidence that Georgia as a whole is growing more rapidly than the other four states, with the City of Atlanta growing as its suburbs also grow.

A “normal” inequality

This all seems pretty banal to me.

There are, unfortunately, many cases in which the structure of local government leads to underinvestment in services that benefit low-income communities — especially when the communities in question are largely African-American. Part of the reason that the inequality is unusually bad when it comes to law enforcement services is that the tradition of hyper-localism is much more deeply entrenched than it is even in areas like education and land use. If policing in Louisiana were a state function, I think it would strike almost everyone as immediately obvious that allocating officers the way they do doesn’t make sense. But it’s not a state function, so in a place with stark partisan sorting and racial polarization, you get the mentality that the job of policing is to contain crime in New Orleans rather than improve statewide public safety. This leaves Louisiana as a persistently very high-crime state with a very high incarceration rate, because they are massively underinvesting in prevention.

But the flip side is that while it’s not shocking to find public services under-provided to marginalized communities, you don’t have the typical patterns of objection to this typical pattern of inequality.

One reason for that is that on both the right and the left, we see persistent confusion between the case for proactive policing and the case for racial profiling. White conservatives push, both explicitly and implicitly, to have more racial discrimination in police conduct, which they try to justify as addressing valid conservatives. Black people respond negatively to that idea, as I think anyone would. But “police shouldn’t do racial discrimination” and “police shouldn’t do anything” are different ideas. When I was a kid in New York, my friends and I got picked up by the cops for drinking beer on a park bench, and then we got stopped by truant officers while we were cutting school to show up for our court appointment. The officers in both cases probably could have correctly guessed based on racial stereotyping that we were not carrying concealed handguns and didn’t have outstanding warrants for violent crimes. But the right way to implement a “quality of life” policing surge is to enforce the rules evenhandedly, not to racially discriminate.

The other thing, though, is that criminal justice reform groups got it into their heads at some point that policing drives “mass incarceration,” which they oppose. This is an analytic error that has driven a lot of bad policy. When you increase the odds of detection, people commit fewer crimes, and you end up incarcerating fewer people. There are privacy rights arguments against things like surveillance cameras, DNA databases, and other things that make it easier to catch people who’ve committed crimes, but this stuff reduces incarceration. Chalfin and Jacob Kaplan have a paper showing this specifically with regard to police staffing, but it’s a pretty general point.

One way to think about the case for reallocation, in fact, is that it sets a virtuous cycle in motion. In Period I, the more efficient allocation of policing resources drives overall crime down (even though it does go up in some places), which reduces incarceration and saves money. Then in Period II, those fiscal savings can be put into additional policing to compensate places that lost officers in Period I. You end up with less crime everywhere, more police officers and fewer prison guards, less incarceration, and a larger legitimate labor force.

No comments:

Post a Comment

Note: Only a member of this blog may post a comment.