Improve student “tracking” don’t eliminate it

The goal should be to push more kids into more challenging work

I’m the parent of an elementary school-aged child, so a subject that I hear a lot of arguing about in real life is the idea of “tracking” (or “detracking”) in public school systems. And listening to these conversations over the years, I’ve noticed three things about how people talk about this stuff.

One is that participants in these arguments seem to have very little consensus as to what it is exactly that they mean by tracking. The United States is a large country with such a decentralized school system that there is no canonical practice of tracking or detracking.

The second is that gut reactions to these ideas are very heavily influenced by framing. I witnessed a discussion about education issues recently in which one person said that it would help a certain set of schools if they were to introduce “advanced coursework.” Lots of people seemed to like that idea. But then someone else said oh no, she’s really talking about tracking, which provoked a turn against it. The original speaker countered that absolutely not, there would be no tracking at all, it’s just that there would be some coursework that was more advanced that students could enroll in if they wanted. Then, the conversation moved on to other things. Personally, I was inclined to agree with both the speaker who proposed the advanced coursework and with the speaker who said the advanced coursework amounted to tracking. But what do I know? Words can mean different things to different people, and the woman wasn’t offering a super-detailed proposal.

The third thing is that two (bad) leftist notions hang over this whole conversation like a dark cloud.

One is a gut-level hostility to any form of testing or assessment. If you believe that standardized testing is per se racist, you’re going to struggle with any system that attempts to sort students, since sorting without a standardized test opens the door to extremely high levels of bias. The other is a kind of dogmatic racialism which insists that anything you do has to create perfect demographic balance relative to the underlying population. School quality matters, and it matters most for poor kids. But it doesn’t matter so much that schools are capable of creating a situation in which quality schooling perfectly equalizes outcomes regardless of background conditions —because those background conditions matter even more. That’s an absurd standard to set for egalitarian policy.

What schools should aim for is a policy that raises everyone up to a reasonable baseline level and that allows all students to thrive, including making sure that academically talented kids from poor or otherwise disadvantaged backgrounds don’t get lost in the shuffle. That means looking for systems that improve on the potential blindspots of a program of differentiated instruction, not systems that abandon the idea.

You can’t treat everyone the same

Anne-Helen Peterson published a piece recently titled “The Case for Detracking” that I think exemplifies some of the ways this discourse tends to go awry.

First, Peterson writes about her own background:

I was a very bored kid for most of school and craved any sort of tracking. Fantasized about it. The one day a week I did get it in elementary school — a well-intentioned but faulty afternoon Gifted and Talented program — felt precious beyond measure. So as an adult, I’ve spent a lot of time unlearning the understanding that “untracked” means “unchallenging for me.”

Given how sensitive people are to framing, I think the traditional decision in the United States to characterize certain academic programs as being for “gifted and talented” children has been borderline catastrophic. Imagine you were given a random group of 200 American teenagers and were told you need to organize them into eight different Spanish classes. Absolutely nobody would decide that the smart way to do this is to divide them up by age. Some of them would be fluent Spanish speakers and some of them would speak no Spanish at all. Others would have learned some rudimentary Spanish in school but not speak it very well. You would want to assess their Spanish language ability and slot them into the appropriate class.

And you definitely wouldn’t put a shiny “gifted” label on the fluent Spanish speakers and tell the world that the beginners are stupid. Lots of smart people don’t speak Spanish! And just because they don’t currently doesn’t mean they can’t learn to!

It is true that, to the best of my understanding, some people really do have a gift for learning languages. Humans are equal in the eyes of God and in the eyes of the law, not in our capabilities or our skills. But from an instructional point of view, the thing you need to do here is assess students’ Spanish language skills, not their “giftedness.” And, of course, precisely because the point here is not to designate certain people as “gifted,” there is no upside to being misclassified into an inappropriately advanced foreign language class. It’s better for everyone to have the right material be taught to the right students, which I think emerges clearly if you can avoid toxic framing.

My son’s cohort was in kindergarten for the bulk of the pandemic school closures, so we’ve known lots of kids who struggled in first and second grade learning to read. And something I’ve noticed among my peers it that every parent whose struggling reader was offered extra help and support from the school welcomed it.

But if the school had instead assessed all the kids and decided those in the top half were “gifted” and the others were dummies, then there would obviously have been enormous backlash. The fact is, though, they did do an assessment and then they assigned different instructional programs to different kids based in part on the results of that assessment. It really wasn’t “tracking” (and I don’t see any reason to track second graders), but even in totally non-tracked classrooms, they have various pull-outs and push-ins and specialized support. Which is just important to put on the table because, on some level, I think everyone recognizes the need for differentiated instruction. It just becomes a question of how you organize it.

Leveling up or leveling down

Peterson’s piece is built around an interview with anti-tracking expert Margaret Thornton, who pretty clearly does believe that kids need differentiated instruction. What she’s talking about is finding ways to deliver that differentiated instruction inside a singular classroom.

On its face, that seems a little odd.

As she makes very clear, this is hard work and logistically difficult! In a small town, of course, a school might have no choice. But why should a large urban or suburban school make teachers sort their students inside their classrooms rather than between classrooms?

Thornton raises the specific concern that at her prior tracked school, kids on the “good” track got the benefit of taking AP classes, while kids on the “bad” track did not. And I think that framing the concern around this kind of specific complaint — there are kids being wrongly kept out of AP classes — is more likely to lead to solutions. But you wouldn’t want to grab kids at random and toss them into an AP French Language class. I took that test after my junior year in high school, but I’d been taking French classes since fifth grade. It’s a hard class; you need to be prepared.

The risk is that in practice, detracking may result in leveling everyone down. Instead of it being unfair that some kids take the AP and others don’t, now nobody takes the AP class. That’s not exactly what happened when San Francisco moved to detrack its math classes, but it is basically what happened — every public school student lost access to certain advanced math work so the richer, savvier parents hired tutors or other outside options. Smart kids with working class parents who don’t have the time, resources, or inclination to work around the system suffered.

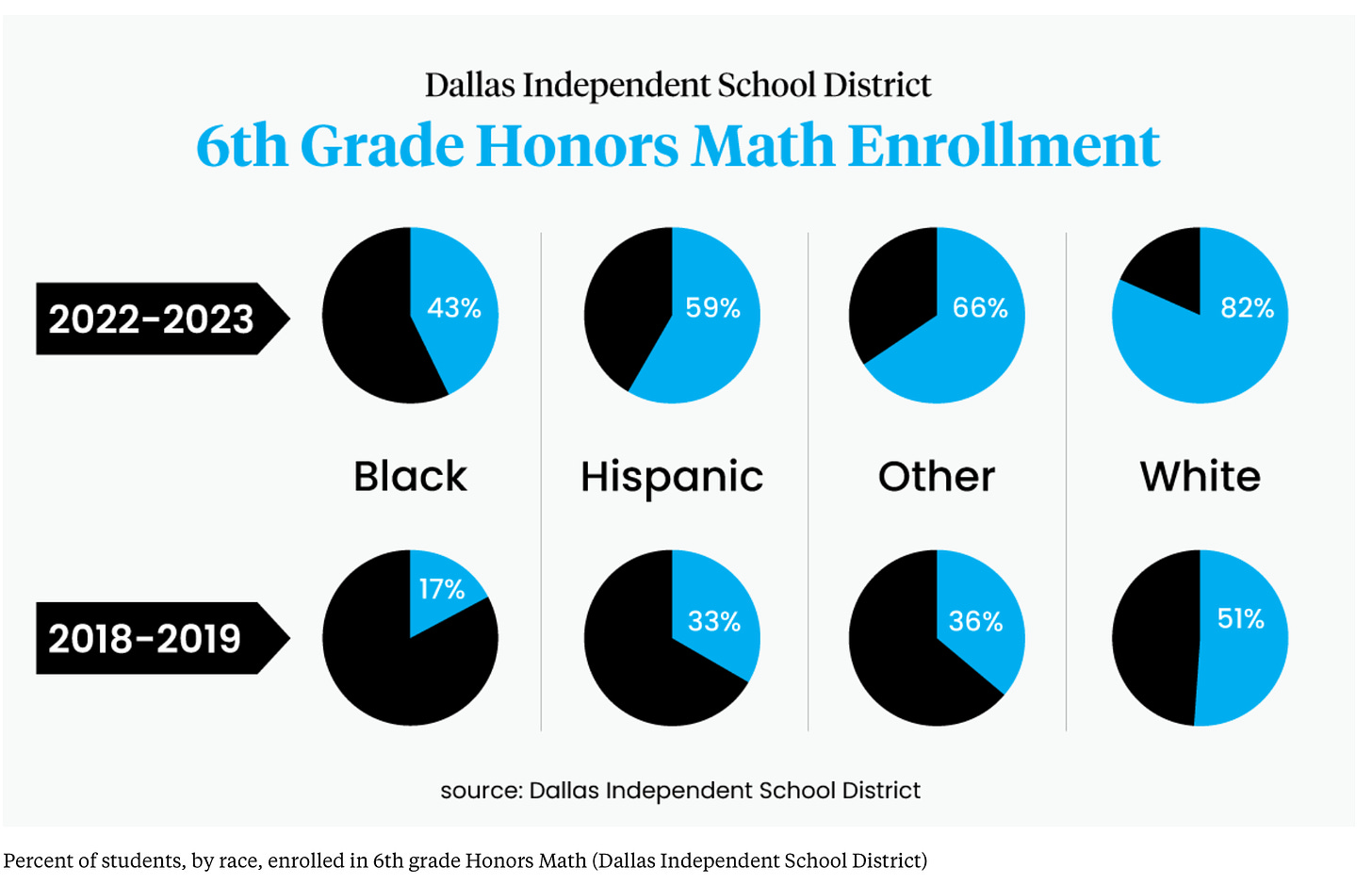

By contrast, back in 2019, Dallas changed its system for middle school honors math, but in the opposite direction. It used to be that to take the honors class, students needed a teacher recommendation or an affirmative parental opt-in. They switched to a new system of auto-enrollment based on test scores, with the option to opt out of the honors class. It turns out that defaults matter a lot, and honors enrollment soared after the switch. Even with this increase in enrollment, the pass rate remained the same as well.

This seems good. Texas is going to do it statewide, and so did North Carolina.

The key thing is that these schools are ditching an unwarranted scarcity mindset around tough math classes. You can only shove so many students into the honors math classroom, but it’s not like it requires expensive renovation to turn more classrooms into “honors” classrooms. You just change the course material.

But even though you can certainly put an egalitarian gloss on this — the share of Black kids taking the honors math class went up 250 percent! — it’s still the case that even after the reform, the honors classes are a lot whiter than the non-honors classes. If elected leaders are unwilling to accept that this is beyond the school’s ability to fully prevent (even if steps like the ones taken in Dallas can improve it), they are inevitably going to find themselves following the leveling-down path of Cambridge, MA, which scrapped middle school algebra classes in the name of equity only to eventually (and rightly) reverse course after it didn’t work well.1

Implementation details matter

DC Public Schools are moving in the Dallas direction, aiming to shift the default to a track where students take algebra in 8th grade and calculus by the end of high school.

This is the right idea, but the implementation details are less clear to me. The new strategic plan document sounds good, but there are no specific criteria for who is going to be taking the 8th Grade algebra.

Another info box in the plan identifies doubling the share of students who take Algebra 1 in middle school as the metric of success. This is directionally absolutely the right change, leveling up rather than leveling down. But I’m still curious, both as a journalist and as a parent of a current third grader, about the specific mechanics. After all, what really matters at the end of the day isn’t what the class is called, but what is actually taught in the class — you want to see students given challenging assignments and able to complete them. Hopefully that’s what will happen.

One very unfortunate aspect of the way these debates have played out is that it’s very hard to tell, from 50,000 feet, whether someone who says we need to improve equity in our accelerated math classes actually means something like Dallas or DC’s default enrollment or something like Cambridge and San Francisco leveling down. It’s further confused by the fact that one set of parents likes to hear this process described as “tracking” and another set hates to hear things described that way. It’s hard enough coming up with policies that work well — needing to message them differently to different audiences is a nightmare.

Fundamentally, though, I think the anti-tracking dogmatists tend to blind themselves to the inevitability of sorting. If the school system prohibits differentiation by classroom, then you still have the old standby of neighborhood-level sorting and residential segregation to rely on. That ultimately screws poor kids, makes housing markets dysfunctional, and unleashed additional layers of economy-wrecking NIMBYism. There are good ways to make advanced coursework more accessible and more fair, ways that do much more to promote equality than the faux-equality of leveling down. But you do need to be realistic about what a school system can be expected to achieve.

No comments:

Post a Comment

Note: Only a member of this blog may post a comment.