Monday, December 23, 2019

Impeachment fits Trump's populist strategy perfectly. Mischiefs of Faction. Hans Noel

Not ready for 2020: A ‘look back’ at America’s worst year before it even starts by Will Bunch

Not ready for 2020: A ‘look back’ at America’s worst year before it even starts | Will Bunch

Friday, December 20, 2019

A Decade of Liberal Delusion and FailureThe New Republic / by Alex Pareene

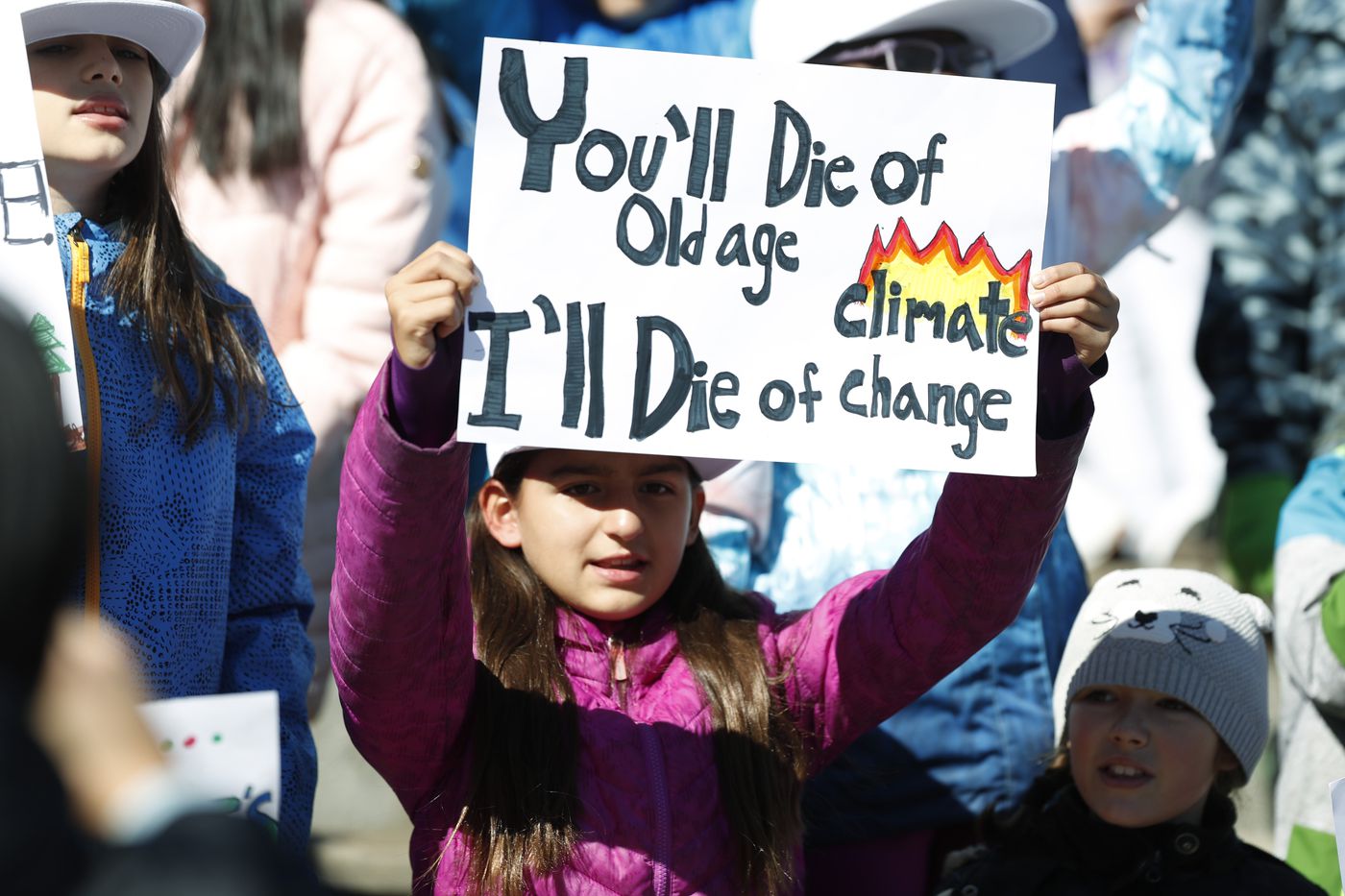

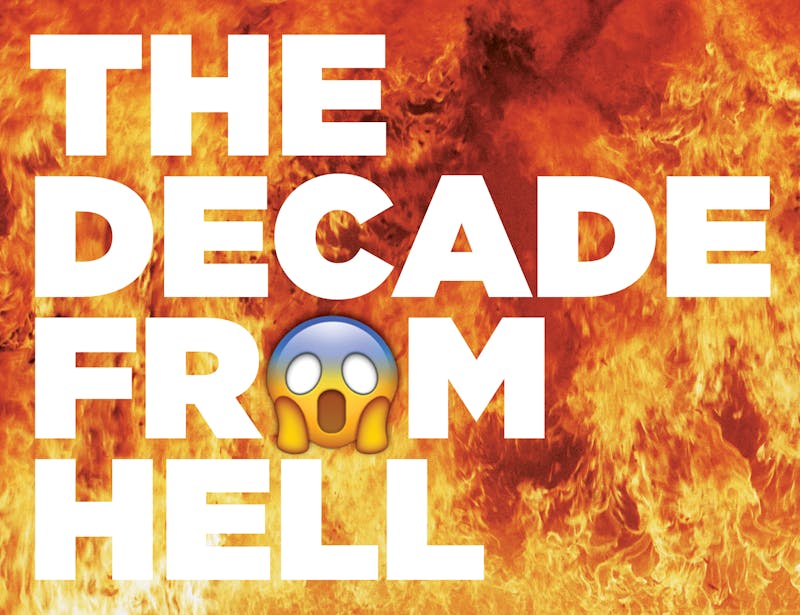

Welcome to The Decade From Hell, our look back at an arbitrary 10-year period that began with a great outpouring of hope and ended in a cavalcade of despair.

As 2009 ended, the editors of this magazine at the time took their measure of the first year of Barack Obama’s presidency and declared it, with some reservations, a modest success. “All of this might not exactly place him in the pantheon next Franklin Roosevelt,” they said of his major domestic achievements (the stimulus package, primarily, as the Affordable Care Act had not yet been signed). “But it’s not a bad start, given all the constraints of the political system (and global order) in which he works.”

That was the broad consensus of American liberals at the time, ranging from nearly the most progressive to nearly the most neoliberal. Over the ensuing years, that consensus would crack and eventually shatter under the weight of one disappointment after another. The story of American politics over the past decade is that of a political party on the cusp of enduring power and world-historical social reform, and how these once-imaginable outcomes were methodically squandered.

The bulk of that unsigned New Republic editorial in 2009 was dedicated to Obama’s foreign policy, specifically the question of whether he was waging enough war. The conclusion: He was. The editors praised “the escalation of the war in Afghanistan” as “the most consequential action of the first year of his presidency,” even though it “offended the base of his party and possibly injured his future political prospects. On strategic grounds, we believe he made the right choice. But the thoroughness and logic of the process by which he arrived at this decision double our confidence in that choice. The is exactly the type of pragmatism and non-ideological policymaking that sentient humans have craved after the Bush years.” (Sure, escalate the endless wars—but for god’s sake, please do it non-ideologically.)

In December of this year, The Washington Postobtained thousands of pages of documents from a government oversight project called “Lessons Learned,” which included interviews with more than 600 people involved in the war in Afghanistan at some point over its 18-year history. An interview with a National Security Council official described, according to the Post, “constant pressure from the Obama White House and Pentagon to produce figures to show the troop surge of 2009 to 2011 was working, despite hard evidence to the contrary.” Nearly every piece of data used over the last decade to try to convince Americans that the war was going well, or even going according to any sort of coherent logic or reason, was phony or meaningless.

“I don’t want to be going to Walter Reed for another eight years,” Obama reportedly said in 2009, as he struggled with the decision to escalate the war. The president, and his closest advisers, were determined to avoid the mistakes of Vietnam. Since then, overwhelmed by billionsin U.S. “aid,” the country has sunk into kleptocracy. Last year, according to the United Nations, was the single deadliest year of the war for Afghan civilians. Today, around 13,000 American service members remain in Afghanistan. The Trump administration is attempting to negotiate a peace with the Taliban that would leave them in charge of the country, just as they were prior to America’s invasion. The war Afghanistan may finally end, but not before the close of this decade that began with that oh-so-carefully-considered decision to escalate it.

“We Are All Socialists Now,” Newsweek declaredon its cover in early 2009, when it was still part of the prestige press (it is currently run by a different sort of cult). Editor Jon Meacham, elucidating the usual historical and political amnesia of airport bookstore historians, justified the claim by writing that “for the foreseeable future Americans will be more engaged with questions about how to manage a mixed economy than about whether we should have one.” A mixed economy run according to Keynesian principles was, you may recall from reading slightly more rigorous historians, the primary alternative to socialism on offer in the West throughout the twentieth century.

The stimulus had been large (if not large enough), but with $288 billion of it dedicated to tax credits and incentives for individuals and businesses, it scarcely resembled socialism. Indeed, rather than giving Americans a greater hand in managing the economy, much of it was designed to be almost invisible. This was intentional. In the May 6, 2009, issue of The New Republic, Franklin Foer and Noam Scheiber described Obama’s “Nudge-ocracy,” a belief, inspired by behavioral economics, that the best way for the government to create good outcomes for the people was not through “heavy-handed market interventions,” but via technocratic attempts to change the behavior of individuals and the incentives of market actors.

The problem with an unseen stimulus is that no one thinks it’s helping them. Obama provided tax relief for nearly every working American, but instead of sending citizens a check, as George W. Bush had done, his economists decided to structure it as a payroll tax cut, subtly increasing the size of everyone’s paycheck. The administration then intentionally did not advertise the fact that they had given nearly every working American a tax cut, in the hopes that people would be nudged into spending, rather than saving, that extra cash. Predictably, in 2010, one poll showed that only 12 percent of Americans believed they’d received a tax cut; 24 percent thought Obama had raised their taxes.

The flaw in this strategy was apparent to another author at this magazine. In late 2009, John B. Judis foresaw a presidency in serious political trouble, because Obama’s fortunes were tied not just to the state of the economy, or even economic trends, but to people’s perceptions of the state of the economy. Noting how Roosevelt “dramatized the New Deal’s contribution to the economy” by creating “colorful new agencies,” thereby “ensuring that Roosevelt was given credit for the rise in employment,” Judis called on Obama to “introduce programs that provide jobs and capture the public’s imagination.” He also suggested the president “turn a deaf ear to those who are calling for fiscal responsibility. He should keep pouring money into jobs and into the pockets of people who will spend until the unemployment rate begins going down and wages begin going up.... And, whatever he does to try to mend the economy, Obama should never stop loudly trumpeting his efforts—so that he is able to reap the credit when improvements occur.”

What Judis didn’t consider, though, was that Obama didn’t want to do any of those things. The president, along with economists who worked for him like Austan Goolsbee and Tim Geithner, all pointedly rejected comparisons to Roosevelt, based in part on a seemingly inaccurate understanding of the history of his first term, but also seemingly based on aesthetics: Roosevelt liked to wrestle his enemies in public, and Team Obama preferred to be above it all. It’s hard to remember now how wise everyone made it sound that the president and his team intentionally avoided doing things they worried would be too popular, but there would not be another New Deal.

Indeed, instead of ostentatious acts of helping people, the administration almost preferred being seen standing athwart attempts to provide relief. A program that was supposed to help underwater homeowners turned down 70 percent of those applying for permanent loan modifications, even as over six million families lost their homes. The point of the program was never actually to help people stay in their homes, of course; it was to preserve the finance industry by spacing out foreclosures. In the end, they achieved their aim: The banks today are as profitable as ever, while more households are renting than in 50 years.

By far the most effective part of the Affordable Care Act, in terms of helping Americans get care, was simply expanding Medicaid. But what many Democrats and liberals were most excited about were the bill’s many experimental and technocratic attempts to “bend the cost curve”—reduce costs without price controls—and “improve quality,” mainly by encouraging insurers, with incentives, to strive for outcomes that market forces alone weren’t incentivizing them to aim for. The signature example of this may be the “Cadillac tax,” which was designed to nudge companies to force employees onto cheaper insurance plans with greater cost sharing—a tax built on the belief that one of the primary drivers of health care cost inflation was people taking advantage of their too-generous employers and greedily consuming more health care than they needed. The tax never went into effect. The individual mandate, similarly designed to force the healthiest young invincibles to enter the market to bring down costs, is equally dead. And a decade into the ACA, it has become more apparent than ever that the best way to reduce America’s absurd healthcare costs would simply be a single-payer program.

That is not to say that the ACA did not end up having the significant long-term political ramifications its drafters promised it would. The primary non-Medicaid structure of the ACA, with its means-tested subsidies to purchase private insurance, had the predictable effect of convincing some of its beneficiaries that Obama and the Democratic Party had nothing to do with the government assistance they weren’t sure they were getting. Then, as costs rose and rose over the decade, that structure also had the predictable effect of making people who receive partially subsidized private care resentful of those poor enough to qualify for Medicaid.

Much of the decade we have just endured has shown how the Democratic addiction to dispensing benefits through the tax code in complicated, indirect ways—combined with the usual insufficiency of these benefits—was nearly perfectly designed to foment mass resentment of others, imagined or not, who might secretly be getting the Good Benefits. The political scientist Suzanne Mettler coined the term “the submerged state” in 2010 to refer to the jungle of hidden government “programs” designed not to call attention to themselves, often perpetuated not because they are still helping the neediest, but because they are lucrative to the finance, insurance, and/or real estate industries. One of her illustrations of the effect of the submerged state is a graph showing how many people who used particular government programs admitted so only after first telling researchers they’d received no assistance.

That nearly 40 percent of people on Medicare claimed this is likely attributable to ideology (and the fact that it, like Social Security, was designed to make retirees feel like they had “paid into it”). But when 60 percent of people who used tax-advantaged higher education savings accounts claim they received no government benefits, as they did in her study, it’s probably because tax-advantaged savings accounts are wholly inadequate to the problem of higher education costs. Now combine this with a persistent belief (memorably describedby Ashley C. Ford a few years ago) that minorities—black kids in particular—get to go to college for free by default, and stir in the rise of tuition costs and other expenses due to cutbacks in state investment in education. The result of this cocktail of ignorant biases and inadequate solutions might look something like the year 2019.

In January 2009, Glenn Beck moved from CNN Headline News, where his show averaged367,000 nightly viewers, to Fox News. By the following March, Beck’s Fox show was averaging 2.8 million viewers, according to the Post’s Howard Kurtz. Kurtz was reporting on divisions within Fox over Beck, who had inspired an advertiser boycott after saying Obama had a “deep-seated hatred for white people or the white culture.” By the next year, Ailes had had enough and severed ties with Beck, while Kurtz bemoaned that the broader media atmosphere that had produced Beck would live on. “It’s a short distance between Beck’s nuttier theories,” he wrote, “and Donald Trump, celebrity businessman and alleged White House aspirant, jumping on the birther bandwagon.” Kurtz would join Fox News in 2013, where he remains today, alongside colleagues like Tucker Carlton and Sean Hannity.

In October 2009, Michelle Goldberg invited New Republic readers to “meet the next Glenn Beck.” It was none other than Alex Jones, at the time best known (besides to Richard Linklater fans) as a prominent 9/11 “truther” representing the fringe of the fringe. “Until recently,” Goldberg wrote, “Jones’s search for mainstream allies has been less than fruitful.” Goldberg noted that even the conservative firebrand Michelle Malkin—an extreme figure, to be sure, but a thoroughly mainstream one at the time—had castigated then-Representative Ron Paul for appearing on Jones’s show and argued that doing so should disqualify a Republican from appearing at primary debates. But with Obama in office, things were already changing. Fox News’s “senior judicial analyst,” one Andrew Napolitano, had just done a joint broadcast with Jones, boosting his new anti-Obama documentary. Representative Louie Gohmert of Texas had just appeared on his show as well.

Naturally, given his belief that 9/11 was a government conspiracy, Jones had been anti-Bush while Bush was in power, making Jones and his audience useful only to legitimate outsiders like Paul. With Obama in the White House, though, he and the conspiracies he generated could help the conservative movement win back power, and so it was no longer considered beyond the pale to associate with him. As for Malkin, she was fired, in November of this year, by a conservative group for publicly supporting a Holocaust denier, and earlier this month she appeared on a white nationalist YouTube channel and applauded young “alt-right” activists.

The Democrats’ fecklessness, in other words, did not flourish in a partisan vacuum. It has been, at every juncture, inspired and influenced by complete failure of the right to self-police. The American right, like the housing market and the banks and the hedge funds and the health insurers and providers, simply could not be induced to check their basest instincts in the face of an opponent that staked its entire political credibility on the promise that it could make Republicans fall in line with realigned incentives or One Weird Trick. If liberals want to get the next decade right, after the previous one in which we repeatedly failed to save the world while telling ourselves we were doing so, we will need to stop nudging and begin fighting.

Thursday, December 19, 2019

Media fail: The press keeps covering impeachment through the eyes of the Republican Party, by Eric Boehlert

Media fail: The press keeps covering impeachment through the eyes of the Republican Party

Even more stunning was the fact that the Michigan county highlighted by Meet the Press is represented in Congress by Justin Amash who made headlines earlier this year when he left the Republican Party because of Trump's corrupt behavior, and who has since come out in favor of impeachment. Yet network news producers looked at that backdrop, and the fact that 54% of Americans support impeachment according to the most recent Fox News poll, and thought the best approach would be to only ask Republican voters how they felt about impeachment?

If that doesn't pull back the curtain on today's coverage and how it's being told literally through the eyes of the Republican Party, I don't know what does. Wedded to the Republican narrative that impeachment has put Democrats back on their heels and is boosting Trump's standing, the press in recent weeks increasingly resembled a soft landing spot for GOP spin.

On Tuesday, when Trump released an incoherent, paranoid diatribe in the form of a petulant, hate-filled six-page letter in an attempt to answer his impeachment accusers, some observers likened the screed to a would-be Unabomber manifesto, only not as well-written. But the Beltway press? They scrambled to normalize Trump's appalling behavior, describing the shocking display of pity and lies as "resilient" and "fiery."

Meanwhile, the dominant theme in recent days—and it reads like it's straight from the Republican National Committee—is that Democrats from closely divided districts face a looming backlash if they vote to remove Trump from office. But there continues to be virtually no evidence to support that.

Stressing "the quiet hand-wringing" that consumed Democratic leaders, The Washington Post last week insisted the party was "bracing" for Democratic defections when the articles of impeachment are soon voted on by the full House. The clear message was that the Democratic strategy was failing and might soon unravel as internal dissension set it, specifically among moderate Democrats who allegedly feared a voter backlash.

Yet in the end, it looks like one Democrat out of the party's House caucus of 233 members will vote no on impeachment. So much for the "bracing" for defections storyline, and how moderate Democrats were running scared. (Hint: The fact Trump publicly admitted to pressuring a foreign government to investigate his political foe has made the impeachment vote a pretty easy one for Democrats.) In an ironic twist, it turns out the only Democratic member of Congress who clearly faces a looming backlash back home over impeachment is Rep. Jeff Van Drew of New Jersey, who has vowed to vote against removing Trump from office. After polling from his district showed Democratic voters furious over such a move, Van Drew is reportedly considering switching to the Republican Party.

And talk about viewing impeachment only through the eyes of Republicans: Last week The Washington Post published a long article on Rep. Elise Stefanik of New York, examining what the political fallout from impeachment has been for the "moderate" Republican. To determine that answer, the article quoted three Republican officials and zero Democrats. The article quoted Stefanik, but not her Democratic opponent. The Post also interviewed the owner of a local diner who had "set up a shrine to the president—complete with a framed portrait, Trump books and a Trump doll." And guess what? After hearing mostly from Republicans, the Post concluded that impeachment has been working out just fine for the Republican congresswoman. Funny how that works.

Even when reporting on Democrats and impeachment, the framing has consistently been through a Republican prism. "On Verge Of Impeachment Vote, First-Term, Moderate Democrats Weigh A Political Risk," read a recent NPR headline, the type of which has been reproduced by scores of news outlets in recent days and revolves around GOP spin: It's Democrats who find themselves in a bind over impeachment, not Republicans. (Keep in mind, it's a Republican president being impeached.)

By the way, one reason why journalists aren't profiling first-term Republicans from swing districts to examine what the impeachment vote will mean for them is because there virtually are none. Why? Because Republicans got wiped out in those districts in 2018. And why did they get wiped out, especially in the suburbs? Because Trump remains deeply unpopular. Yet against that backdrop, the media claims it's Democrats who are on the defensive?

Half the country supports removing Republican Trump, the most consistently unpopular president in American history, and the press scrambles to explain why that's a problem for Democrats. January will feature the impeachment trial in the Senate. That means journalists still have time to stop telling the impeachment story through the eyes of the GOP.

Eric Boehlert is a veteran progressive writer and media analyst, formerly with Media Matters and Salon. He is the author of Lapdogs: How the Press Rolled Over for Bush and Bloggers on the Bus. You can follow him on Twitter @EricBoehlert.

This post was written and reported through our Daily Kos freelance program.

Facebook Is a Right-Wing Company, Part One Million. The New Republic. by Alex Shephard

On Tuesday, The Wall Street Journal reported that Thiel, a longtime Facebook board member, had become Zuckerberg’s consigliere. With the company’s leadership under fire for its refusal to vet political advertisements’ veracity or limit advertisers’ ability to target ads—in contrast to Google and Twitter, which have taken steps to crack down on misleading content—Thiel has encouraged the embattled Facebook CEO “not to bow to public pressure.” The Journal noted that Thiel was “extending his influence while the company’s board and senior ranks are in flux.”

Once quiet, Thiel’s influence over Facebook has grown louder as the company has tried to navigated a succession of scandals and seen its popularity plummet. His values are driving Facebook as the company doubles down on policies that empower demagogues and despots and disempower the rest of us.

Hauled before the House Judiciary Committee earlier this year to address the Cambridge Analytica scandal, Zuckerberg made the case that his company cared deeply about making the world a better place. “Facebook is an idealistic and optimistic company,” he said. “For most of our existence, we focused on all the good that connecting people can bring.” Zuckerberg and his allies then went on a public relations blitz to convince an increasingly skeptical public that Facebook had learned its lesson.

The rebranding campaign made a warm and fuzzy appeal: Facebook is where you look at pictures of puppies and babies. It’s where you can stay connected with loved ones, wherever they may be. But in private, the company was embracing Thiel’s conservative values.

Much of this has come out via the company’s shifting relationship with the media. Last year, Facebook empowered former Republican Senator Jon Kyl to investigate the conservative claim that Facebook, like other Silicon Valley tech companies, was suppressing speech from the right. Like a similar partnership with the Heritage Foundation, the move may have been intended to bolster the company’s credibility with conservatives. But it backfired, with Kyl blasting the company for not taking conservatives’ concerns about speech seriously, even though those concerns had little to no basis.

Then, in October, Facebook launched a partnership with a number of news outlets. Facebook had become synonymous with the “fake news” problem, and its response was to empower legitimate outlets by launching Facebook News, a tab on its mobile app. But one of Facebook’s new partners was Breitbart, the alt-right hub that regularly publishes racist stories. As The Verge’s Casey Newton noted at the time, “Breitbart was included in the tab precisely for ideological reasons. … Certainly no one at Facebook seems to be suggesting that Breitbart is a reliable producer of high-quality journalism—the argument seems to be rather that it would be poor form to exclude them just because they once (for example) tagged relevant stories with the label ‘black crime.’”

Meanwhile, Zuckerberg’s public rhetoric has gotten more MAGA. He now makes a nationalistic argument on behalf of Facebook: Empower us, or cede ground to China. Defending the company’s digital currency Libra before Congress this summer, Zuckerberg said, “I believe that if America does not lead innovation in the digital currency and payments area, others will. If we fail to act, we could soon see a digital currency controlled by others whose values are dramatically different.”

As it happens, Thiel has been one of Silicon Valley’s leading anti-China voices, arguing in August that Google was helping the country “gain an intelligence advantage” and “penetrate defenses in the relatively new theater of cyberwarfare.”

In October, Zuckerberg delivered a new manifesto for Facebook. While he continued to claim the company was about bringing people together, he also made a free speech absolutist case in defense of his life’s work. “I am here today because I believe we must continue to stand for free expression,” he told an audience at Georgetown University. Facebook, in this telling, could not police its platform out of principle. It could not rid itself of hate speech and manipulative political advertisements aimed at promoting right-wing candidates, even if it wanted to. “I don’t think it’s right for a private company to censor politicians in a democracy,” he said.

For years, Facebook’s public relations team have tried to present Mark Zuckerberg not as the ruthless billionaire he is, but as a compassionate and curious young man seeking to understand the world around him. That has changed over the past year and a half. Facebook has, as many have noted, always been a covertly right-wing company, “hostage to conservative ideas about economics and speech,” as Jacob Silverman wrote in The Baffler. Thanks to Thiel’s influence, it has increasingly become an overtly right-wing one.

Tuesday, December 17, 2019

Yes, parties can become less democratic, too / Mischiefs of Faction / by Seth Masket

Yes, parties can become less democratic, too

State parties change their rules frequently, and they make their rules less democratic almost as often as they make their nominating contests more so.

Wednesday, December 11, 2019

The Cops Are Culture Warriors by Melissa Gira Grant / The New Republic

This sort of counter-campaign has become more common in the Obama and Trump eras. Police have panicked as calls for criminal justice reform have moved to the center of American politics, fueled by decades of popular movements against police brutality and prisons. Just as conservatives, going back to the Nixon era, have used debates over the lawfulness of abortion, homosexuality, and pornography to portray themselves as besieged by a liberal elite, police unions, too, now claim they are on the losing side in an ideological struggle. It may appear strange to see police alongside anti-contraception crusaders, transphobic employers, and Evangelical cake-makers on the supposed front lines of a national clash over values. But it also represents a return to the culture war’s origins.

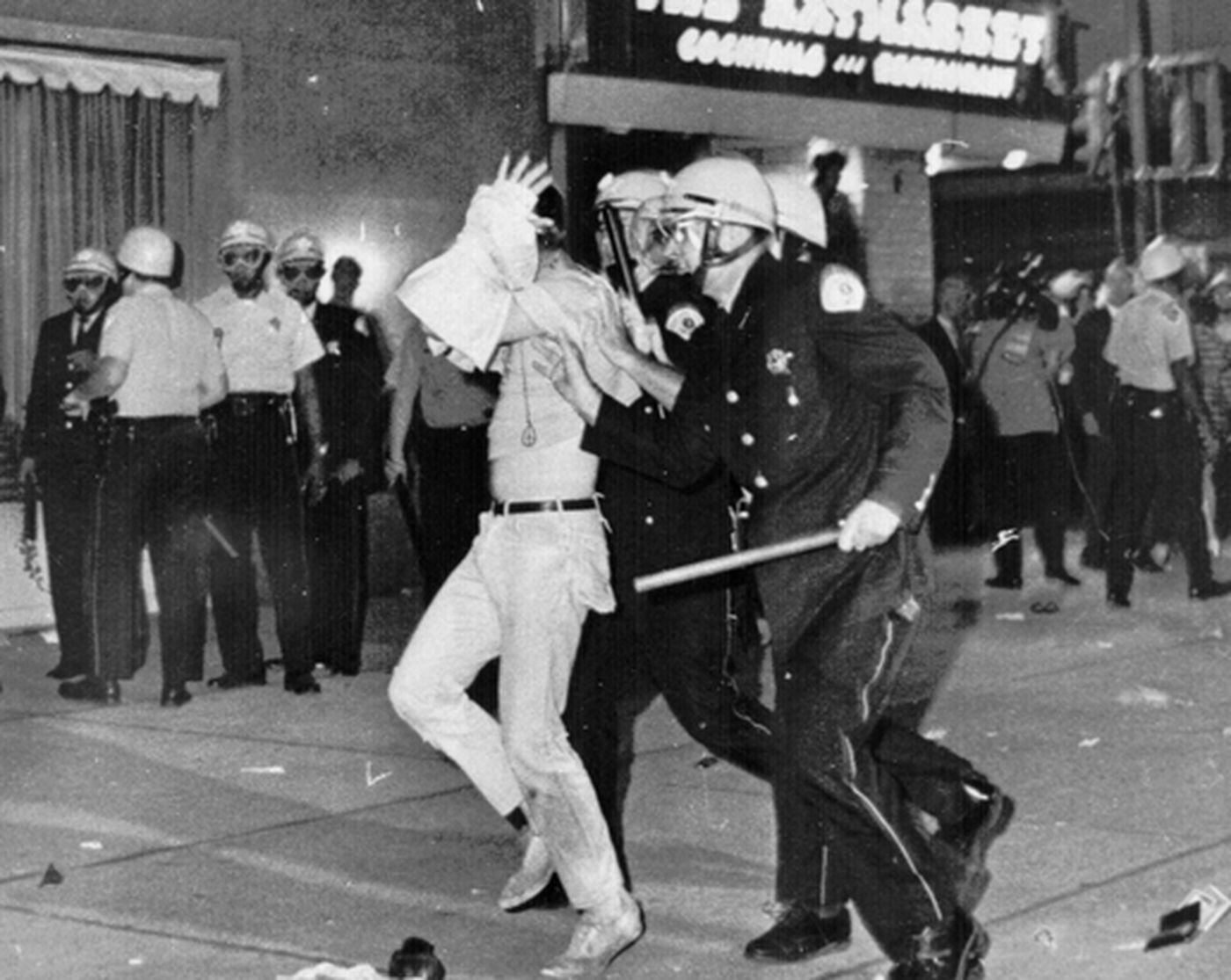

The very idea of the culture war was born out of policing. Though the phrase didn’t come into common usage until the 1990s, anxiety over law and order helped usher Nixon into the White House in 1968. Where today police unions cast Black Lives Matter activists as their persecutors, conservatives under Nixon pointed to black power activists and the anti-war left.

With James Davison Hunter’s 1991 book Culture Wars: The Struggle to Define America, the term “culture war” entered the popular lexicon. Hunter says he was inspired after reading a news story about the arrests of clergy from a range of sometimes warring faiths at an anti-choice protest. He saw the struggle emerging out of 1960s social change as a matter less of specific issues than of something much broader: “progressivism” versus “orthodoxy.”

Throughout the 1990s, many who were at odds with one another when it came to other issues, such as abortion or gay rights, were largely in agreement on defending the power of police—whether that meant uniting against Ice T’s “Cop Killer” song and gangsta rap or more sweeping policy proposals. While governor of Arkansas, Bill Clinton rejected the clemency petition of Ricky Ray Rector, a black man who shot and killed a white police officer before shooting himself, leaving him mentally incapacitated. Clinton took a break from campaigning in New Hampshire in 1992 to return to Arkansas and oversee Rector’s death by lethal injection. Rector asked for part of his last meal to be set aside for later—a sign that he did not fully understand how severely he was to be punished. Yet for backing the execution, Clinton was lauded for being tough on crime.

As president, Clinton would go on to be forever linked with his signature 1994 crime bill, putting more than $9 billion into prisons and adding 100,000 more cops on the streets. The Violent Crime Control and Law Enforcement Act of 1994 also defined 60 new death penalty offenses. Even as the crime rate declined sharply during and since those years, the majority of the American public continued to believe crime was getting worse each year.

The Obama years saw the start of a profound shift. First galvanized by the death of Trayvon Martin in 2012 and his killer’s acquittal in 2013, activists across the country returned to the streets in protest after police killed Eric Garner in New York City and then Michael Brown in Ferguson, Missouri. In demanding accountability from police who kill, the Black Lives Matter movement highlighted the ways in which the system of policing makes such accountability nearly impossible. Police unions, they argued, are critical in shielding police from discipline for brutality and violence. When the officers who killed Brown and Garner were not indicted, activists pointed to the power held by district attorneys—who rely on police to help them win convictions—in convening and persuading grand juries.

It was these activists who helped shift the line marking the acceptable edge of law enforcement critique, and by the 2016 election, Democrats had noticeably backed off from the Clinton-era consensus. Contenders in 2016 made abolishing the death penalty part of their platforms. By then, it was more common to hear that criminal justice reform was a bipartisan issue—albeit in a limited sense, with centrist overlap on a few modest reforms like creating alternatives to pre-trial detention.

Meanwhile, perceptions of crime numbers were falling. Eighty-seven percent of Americans polled in 1993 believed crime had increased from the prior year. In 2018, that number was down to 60 percent. In an administration of “lock her up” chants, accompanied by flagrant and likely illegal presidential abuses of power, tough-on-crime stances have proven hard sells in liberal circles. 2020 Democratic candidates have pledged unprecedentedly progressive criminal justice plans.

As consensus on the power of law enforcement was fracturing, some political observers declared the more classic culture-war issues resolved: “Culture War Is Over,” The American Prospect optimistically proclaimed in 2012. “Same-sex marriage is a non-issue in American politics,” one CNN piece announced in 2014. At the same time, liberals were growing more comfortable with the prospect of criminal justice reform, pushed from their left by grassroots activists. In response, the right—and especially police unions—grew more vocal and vehement in denouncing activists and defeating reform-minded candidates.

In San Francisco this year, police unions opted for a core alt-right conspiracy theory, depicting Chesa Boudin as a puppet of George Soros, who has emerged as a leading donor in prosecutor races across the country. In 2018, San Diego prosecutor Summer Stephan similarly attacked progressive challenger Geneviéve Jones-Wright by promoting an attack website juxtaposing images of antifa and Black Lives Matter activists with a Soros portrait—one of many such attempts to link Soros with anti-police sentiment. The site went offline in 2018, one week after Soros was mailed a pipe bomb.

In November, an elected member of the school board in Corvallis, Oregon, Brandy Fortson, started receiving death threats after two of their tweets were circulated by the official Twitter accounts of the Fraternal Order of Police (the nation’s largest police organization) and the Oregon state Republican Party. “Hey kids, always remember that all cops are bastards,” read one of the tweets, which Fortson said was in response to Texas police arresting a man for allegedly stealing a shopping cart to take his groceries home. “Sex work is work,” read the other tweet Fortson’s critics offered as evidence that they should be removed from office.

“You should not be involved in the development of our nations [sic] children,” the FOP tweeted, also attempting to lecture Fortson, who is queer and nonbinary (using the pronouns they/them) and already a likely target of harassment, on tolerance: “Mx. Fortson, as a society, we raise our kids to accept, not hate, people from all walks, regardless of race, sexual orientation, gender or career choice. Your values clearly do not reflect this.”

As might be expected when a national group targets a nonbinary school board member in a town of 55,000, the results were swift and frightening. One caller, Fortson told a local reporter, said “he was looking forward to shooting my child in the head at school and watching her brains get strewn about on the sidewalk while he laughed and I cried.” Even after Fortson resigned, the threats continued. Andy Ngo, who uses his Twitter account to share the names and photos of activists he claims are violent, directed his followers to Fortson. Within 15 minutes of Ngo’s tweets, Fortson said, they received “10 or 11 death threats.”

Police unions may engage in such aggressive tactics in part because they accurately perceive their powerful allies to be slipping away. In 2019, no realm of politics remains a criticism-free zone for cops. Michael Bloomberg’s tardy entrance into the Democratic primary came with an acknowledgment that his tough-on-crime turn as New York City mayor—like his pride in the unconstitutional police practice of stop-and-frisk—was perhaps a liability. “I got something important really wrong,” Bloomberg said from the pulpit of a black megachurch in Brooklyn. “I didn’t understand back then the full impact that stops were having on the black and Latino communities.” Even if the apology is insincere—Bloomberg still defended the policy earlier this year—the fact that he feels he has to make this kind of statement illustrates how the lines in the police culture war have shifted.

In her run at the 2020 Democratic nomination, Kamala Harris, a former San Francisco district attorney and California state attorney general, struggled to square her prosecutor past with the new political reality for Democrats. Previously, Harris had portrayed herself as someone who is neither tough nor soft but “smart” on crime. At times, she tried to depict herself as a reformer, though that is not how she was regarded as a prosecutor. With her campaign in disarray, her poll numbers slipping behind the front-running white candidates, Harris announced her withdrawal from the race on Tuesday.

Once, cops could count on establishment and even liberal media to back them—to point out, for example, that Michael Brown, as The New York Times printed in 2014, was “no angel.” That, too, has changed: In November, when the Times editorial board criticized police and prosecutors’ attempts to block modest bail and discovery reform measures, they were blunt and prescriptive, calling the efforts “A Sad Last Gasp Against Criminal Justice Reform.”

The less taboo it has become for anyone with some modicum of power to critique the police, the more law enforcement and their backers have moved to police the boundaries of permissible debate about their power. This Tuesday, Attorney General Bill Barr even suggested that those who don’t offer “support and respect” to cops could be deprived of police protection. Despite police and their advocates’ assertions of victimhood, police are far from marginalized targets, oppressed by reformers, abolitionists, or even prosecutors: They still have the full force of the state behind them. And that’s precisely why police are so invested in this war—to keep the state out of the hands of reform-minded public officials and those who seek to elect them.