Turning politics up to 11: Russian disinformation distorts American and European democracy

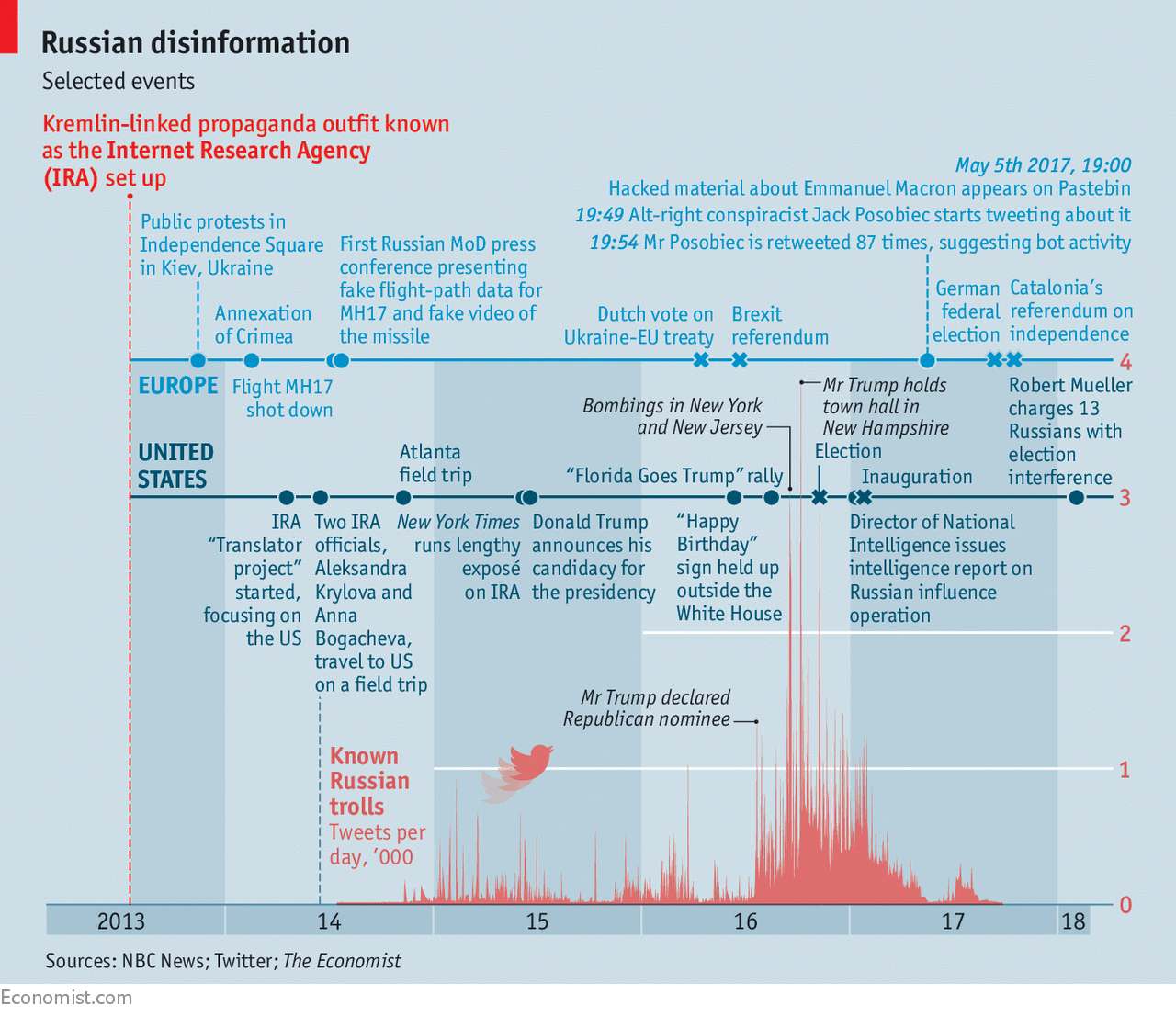

This bizarre story is one of the details which make the grand-jury indictment filed in Washington, DC, on February 16th so fascinating, as well as deeply troubling. The indictment was filed by Robert Mueller, a former director of the FBI who is now the special counsel charged, as part of his investigation into Russian efforts to interfere with America’s election in 2016, with finding any links between Donald Trump’s election campaign and the Russian government. It charges three companies Mr Prigozhin controlled, including the Internet Research Agency (IRA, see article), and 12 other named Russians with identity theft, conspiracy to commit wire and bank fraud and conspiracy to defraud America by “impairing, obstructing and defeating the lawful governmental functions of the United States”.

Using fake social-media personas, the Russians tried to depress turnout among blacks and Muslims, encourage third-party voting and convince people of widespread voter fraud; their actions were designed to benefit Bernie Sanders, who lost the Democratic nomination to Hillary Clinton, and Mr Trump. “Many” of the social- media groups created as part of the operation, Mr Mueller says, had more than 100,000 followers. The Russians organised and co-ordinated rallies in several states, such as a “Florida Goes Trump” day on August 20th. They were in touch with “US activists” (perhaps it was one of them who sent those birthday greetings from Lafayette Park). These included “unwitting members, volunteers, and supporters of the Trump campaign”.

The indictment says nothing about the degree to which witting parts of Mr Trump’s campaign may have encouraged these actions, though it does refer to co-conspirators “known...to the Grand Jury”. Nor does it delve into the question of Russian responsibility for hacking the Democratic National Committee. But it is an unprecedentedly thorough, forensic account of a scheme that was of a piece with the covert propaganda and influence operations Mr Putin now wages against democracies around the world. Sometimes, these interventions seek to advance immediate foreign-policy goals. They also have a broader, long-term aim: weakening Western democracies by undermining trust in institutions and dividing their citizens against each other.

In this, they are working with the grain of the times. Social media are designed to hijack their users’ attention. That makes them excellent conduits for the dissemination of lies and for the encouragement of animosity. Russia’s manipulations make use of these features (from the point of view of those who would make money from social media) or bugs (from the point of view of people who would like political lying to be kept to a minimum) in much the same way as unscrupulous political campaigns that are not subject to malign outside influence. This makes the effects of Russia’s actions hard to gauge. In many cases they may be minor. But that does not make their intent less hostile, or their evolving threat less disturbing. Nor does it make them easier to counter. Indeed, the public acknowledgment of such conspiracies’ existence can help foment the divisions they seek to exploit.

The use of disinformation—“active measures”, in the KGB jargon of Mr Putin’s professional past—to weaken the West was a constant of Soviet policy, one that the would-be victims fought back against with similar weaponry. In the 1960s the KGB-funded Liberty Book Club published the first title alleging that John F. Kennedy’s assassination was a conspiracy. Later the KGB forged a letter from Lee Harvey Oswald in an attempt to connect the plot to the CIA. Mostly this had little effect. In the 1970s forged pamphlets designed to start a war between the Black Panthers and the Jewish Defence League failed to do so. But some worked. The CIA did not invent HIV in a biological-weapons lab, but the KGB did invent the story, and many people still believe it.

After the collapse of the Soviet Union the use of active measures against the West went into hiatus, though they still found use against some countries of the former Soviet Union. Then, in December 2011, people took to the streets in protest against Mr Putin. Mr Putin blamed Mrs Clinton, then America’s Secretary of State.

The Maidan uprising in Ukraine in February 2014, the subsequent Russian-backed fighting in the east of the country and the annexation of Crimea moved things up a gear. Kremlin-controlled media claimed that Ukraine’s government was dominated by fascists and that its armed forces were committing atrocities. Russian trolls spread the stories on Twitter, Facebook and the Russian social-media platform VKontakte.

In July of that year 298 people were killed when Malaysia Airlines flight MH17 was shot down by a Russian missile over eastern Ukraine. The Kremlin responded with a barrage of disinformation blaming Ukraine. Its defence ministry hosted a press conference at which it presented fake data on the plane’s flight path, as well as a tampered video which made it appear that the lorry carrying the missile had passed through Ukrainian-controlled territory. As European public opinion turned sharply anti-Russian, the Kremlin stepped up efforts at covert influence well beyond Ukraine proper.

The cyber elements of such activities get the most attention, but much of Russia’s activity consists of techniques from the pre-digital Soviet manual: marshalling human assets, be they active spies or sympathetic activists; funding organisations that may be helpful; and attempting to influence the media agenda.

Sponsored visits to Russia have bolstered relationships with politicians including Nick Griffin, once the leader of the fascist British National Party; Frank Creyelman, a member of the Flemish parliament for the far-right Vlaams Belang party; and Marton Gyongyosi, a leader of Hungary’s far-right Jobbik party. Last September an MP from the far-right Sweden Democrats (SD), Pavel Gamov, managed to get kicked off one of these junkets by demanding that his hosts pay his bar tab and other untoward expenses. (The SD expelled him, too.)

Broadcasters like RT and Sputnik spread disinformation that furthers Mr Putin’s ends and slant news stories in ways that play up their divisiveness. Plenty of news outlets with greater reach do the latter; but one area where Russian active measures go further is in the use of straight-up forgery. Martin Kragh, a Swedish security expert, describes more than 20 forgeries that have made news in recent years. One was a fake letter supposedly written by Sweden’s defence minister, offering to sell artillery to Ukraine. A second purported to contain evidence of a conspiracy to install Carl Bildt, a former Swedish foreign minister, as Ukraine’s prime minister. The forgeries often appeared first on Russian-language websites, or were placed on social media by a pro-Russian account. As Mr Kragh notes, such fakes often continue to circulate on social media long after they are debunked.

It is in assuring such continued circulation that outfits like the IRA play a role, setting up automated accounts—“bots”—that promulgate messages to specific groups and individuals. Last November NATO’s Stratcom Centre of Excellence in Riga, which studies disinformation, found that 70% of Russian-language social-media communication about NATO in the Baltic states seemed to be generated by bots. A study of social media during the Brexit campaign by 89Up, a consultancy, found that Russian bots delivered 10m potential Twitter impressions—about a third of the number generated by the Vote Leave campaign’s Twitter account. Such echoing amplifies the effect of RT and Sputnik stories, which are in general not much watched.

Their all-or-nothing nature makes referendums particularly juicy prizes. At least one in the Netherlands has been targeted. Javier Lesaca, a political scientist at George Washington University, found that RT and Sputnik stories on Catalonia’s independence referendum last year—which took the pro-independence side, as Russia would wish—were retweeted on a vast scale by “Chavista bots” which normally spent their time tweeting messages sympathetic to the Venezuelan government.

Estimating how many bots are out there is hard. Primitive bots give themselves away by tweeting hundreds of times per hour, but newer ones are more sophisticated. Some generate passable natural-language tweets, thus appearing more human; others are hybrids with a human curator who occasionally posts or responds on the account, says Lisa-Maria Neudert, a researcher at the Oxford Internet Institute. It is not always easy to distinguish bots from humans. “Journalists spend a lot of time talking on social media. Sometimes they look almost automated,” she says.

Discovering who controls such accounts is even harder. In America the main work of identifying which bots and troll accounts were run by the IRA has been done by Twitter and Facebook themselves. Independent analysts can try to identify Twitter bots based on their activity patterns, but for Facebook accounts, which are mainly private and post only to their own friends, it can be impossible for anyone outside the company.

“We don’t have a list of Russian troll accounts in Europe, similar to what we have for the US,” acknowledges Ben Nimmo of the Atlantic Council’s Digital Forensic Research Lab (DFRLab), which studies online influence operations. In Germany Mr Nimmo identified a Russian botnet—in this context, a network of mutually reinforcing bots—that amplified right-wing messaging in the week before the German election in September, promoting #Wahlbetrug (“election fraud”) as a hashtag. Beforehand the botnet had spent its time promoting pornography and commercial products. It may have been a freelance rent-a-botnet also available for far-right messaging; it may have been a Russian operation. The difference can be hard to see.

So can the impact of such interventions. Analysts are most confident of ascribing influence when they see a superhuman burst of bot activity followed by a deeper but more leisurely spread deemed to be “organic” (both in the sense of proceeding naturally and being done by flesh not circuits). This is what happened when material stolen from Emmanuel Macron’s campaign was posted shortly before the second round of last May’s French election. An analysis by DFRLab showed that the top ten accounts retweeting links to the material posted more than 1,300 times in the first three hours, with one account posting nearly 150 tweets per hour. Later, says Ms Neudert, the messages began to spread organically. On the other hand, Mr Lesaca’s figures suggest that the retweets of RT and Sputnik by Chavista bots were not taken up by living, breathing Catalans.

Some European countries are trying to strengthen themselves against web-borne disinformation. On a sunny afternoon at the Alessandro Volta junior-middle school in Latina, 50km south of Rome, Massimo Alvisi, who teaches digital literacy, runs through some of the topics the rumbustious children in front of him have covered this year. A visitor asks the class: why do people make things up online, anyway?

“People put up false stories to earn money,” shouts a dark-haired wiseacre at the back. “To create panic!” says another. “To deceive people.” “Just to have fun!”

Mr Alvisi, a history teacher by training, has been leading the digital-literacy classes for two years. He developed his course partly on his own initiative. But the issue has been given a new push. Last year the president of Italy’s Chamber of Deputies, Laura Boldrini, announced a “Basta bufala” programme (fake news, for reasons which appear obscure, is known as “bufala” in Italy). She has herself been a target of online attacks; she has furiously denounced a Northern League senator who shared a baseless post alleging that she had obtained a government job for her brother, a well-known abstract painter.

Italy is an easy target for disinformation; fake news is rife, trust in the authorities low, and some parties like it like that. In last year’s German elections all parties swore off the use of bots (though the AfD dragged its feet). In Italy the Northern League positively encourages bottishness with an app that automatically embeds party postings in supporters’ timelines. The populist Five Star Movement is opposed to anything top-down, including efforts to block fake news (which can indeed, in government hands, look disturbingly like ministries of truth). Its websites and Facebook pages have become Petri dishes for conspiracy theories in the run up to the general election in March.

Sweden, too, is rolling out a national digital-literacy curriculum. Teachers there are particularly impressed by the effect of assignments that get the students to create fake-news campaigns themselves; they dramatically improve students’ awareness of how disinformation works, and how to recognise it. Sweden’s Civil Contingencies Agency (MSB), which is responsible for communications during emergencies and for combating disinformation, runs similar “red teaming” exercises for government agencies, in which staff brainstorm attacks to test their own vulnerabilities.

Its flow chart for handling information attacks looks at the emotions they seek to engender (fear, shock, discouragement) and the tools they employ (trolls, hacks). Identifying the aggressor is not a priority. “Intelligence agencies can handle that. We need to think about the effects,” says Dominik Swiecicki of the MSB. Indeed, in some cases attribution could be counter-productive; saying someone has struck you without having the will, or wherewithal, to strike back can, as America is learning, make you look hopeless.

Robust efforts by platforms such as Facebook and Twitter to monitor trolls, bots and aggressive disinformation campaigns would greatly help all such moves towards resilience. Facebook, for which Russian meddling poses a severe image problem (see article) has promised it will have 20,000 people monitoring abusive content by the end of the year. Twitter’s identification of IRA-linked bots has enabled independent groups to track their activities as they happen, observing them as they seized on topics such as the high-school massacre in Parkland, Florida on February 15th (see article). Governments are pressing them to do more. But, as Ms Neudert observes, “There are massive concerns about freedom of speech.” She says that because of German fines for online hate speech and fake news, “The platforms are ‘over-blocking’ all kinds of content that they are worried might be in any way problematic”. France, Italy and the Netherlands say they too are looking at laws and other measures to combat fake news.

When evidence of the conspiracy first surfaced in 2016, Congressional Republicans refused to agree to a bipartisan statement warning of Russian attempts to breach voting systems. Mr Obama responded to what the intelligence services were telling him with modest warnings and symbolic sanctions, aware that to do more in defence of the election without the support of Republicans might backfire with suspicious voters. After the election, but before Mr Trump’s inauguration, the director of national intelligence issued a report laying out much of the evidence he had seen and warning of its seriousness.

Then things got worse. Mr Trump appears to read allegations of Russian meddling not as national-security threats but as personal attacks—insinuations that without them he would not have won. He lies about the issue, as when he tweeted, “I NEVER said Russia did not meddle in the election” on February 18th, and he has undermined the FBI’s attempts to understand both the conspiracy and its links, if any, to his campaign. He fired James Comey, the FBI’s respected head, after Mr Comey refused to offer him a pledge of personal loyalty. He publicly attacked the bureau after the Florida shooting (see Lexington).

Mr Mueller still has a way to go. He has years of e-mail and social-media communication belonging to the 13 indicted Russian agents and, it appears, unnamed “co-conspirators”. Many expect him soon to indict those responsible for hacking into Democratic servers, and perhaps in doing so link them to organs of the Russian state, or members of Mr Putin’s inner circle. On February 20th Alex van der Zwaan, a lawyer involved in Ukrainian politics and the son-in-law of a Russian oligarch, pleaded guilty to making false statements about his communications with a worker on the Trump campaign. But whatever Mr Mueller finds, the fate of the president will be political, not legal, determined by Congress and, ultimately, the voters.

Unfortunately, when it comes to voting, says Michael Sulmeyer, head of the Belfer Centre’s Cyber Security Project at Harvard, interference looks set to continue. Mr Trump’s intelligence chiefs also expect Russia to try to influence this autumn’s midterm elections—presumably to benefit Republicans, since congressional Democrats are more eager to investigate their meddling. Many states use voting machines vulnerable to hacking (some are turning back to paper to guard against it). The Department of Homeland Security found that Russian hackers tried to breach election systems in 21 states in 2016.

Mr Trump has given no instructions as to how to counter this threat. His refusal to take Russian interference seriously and dismissal of unfavourable reports as “fake news” have made America fertile ground for further disinformation campaigns. They let his supporters deny the facts. A poll published this January found that 49% of Republicans do not believe Russia tried to influence the election in 2016. It would be naive to expect that number now to fall to zero. “If it was the GOAL of Russia to create discord, disruption and chaos,” Mr Trump tweeted on February 17th, “they have succeeded beyond their wildest dreams.” For once, he had it right.